“ONE” is an episode in the fourth season of STAR TREK: VOYAGER, based on an original story premise written by me.

AUTHOR’S NOTES

‘One‘ was an important benchmark in my writing history, as my first ever story sale to a television studio; it was a success made doubly sweet to me, because it was a Star Trek storyline, and I had been a fan of the saga since childhood.

If there’s an instant in my writing career that will never ever leave me, it’s the moment when I first saw an image from the Star Trek: Voyager episode ‘One‘ – it was a shot of the crew, racked up in stasis chambers across the cargo bay, every one of them dormant and sleeping in these coffin-like containers.

What left me speechless about that picture was that it was the very conception I’d had in my mind when I’d originally written the basis for the show, a story premise called ‘Perchance to Dream‘. From the inside of my head to the screen…it was the wonder of television captured for me in a single image.

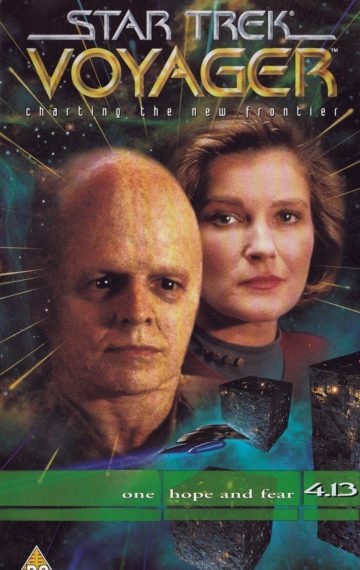

The penultimate episode of Star Trek: Voyager‘s fourth season first aired on 13th May 1998; the show was called ‘One‘, and its plotline centred on the reformed Borg character Seven of Nine as she was forced to pilot the starship alone through a deadly radioactive nebula. The script was the last to be written by executive producer Jeri Taylor before stepping down from the show, and the plotline was drawn from a story pitch that had been my first big-time Hollywood sale.

To explain how it got to there from here, I have to wind back the clock almost a decade… It was the end of January 1998 when the call came. Just like that, with no fanfare or performance, the words I had been waiting to hear for almost one third of my life came beaming across the world to me, from a small office in the Hart building on the Paramount Pictures lot. The dulcet tones of Lolita Fatjo, Star Trek‘s script co-ordinator and pre-production associate told me “Congratulations, Jim! We want to buy your story!” I can remember the curious lack of emotion I felt at the time; I’d rehearsed that moment a thousand times in my mind, and now here it was, and I didn’t punch the air, yell or dance. I just took it coolly and quietly, in a lightly stunned kind of way. It took a long time to sink in.

After a handful of scripts for three different Star Trek shows, dozens of pitches and a fair few rejections, I had finally made the cut and sold a story premise to Voyager. Lolita also informed me that I had the double honour of being the first British writer ever to do so; I felt a swell of pride at that, flying the Union Jack in the Star Trek universe. What began as an idea for a story centred on Robert Picardo’s Doctor character, about madness and despair, would eventually morph into ‘One‘, Taylor’s dynamic and taut script that took Jeri Ryan’s Seven of Nine on a journey into darkness. But it had been a long, strange trip from paper to screen, indeed…

Back in 1989, Paramount initiated a process that was unprecedented in television history. As the third season of Star Trek: The Next Generation began, the production office opened its doors to speculative script submissions from unagented writers – in short, from Star Trek fans. The speculative script (or just ‘spec’) is the screenwriter’s calling card, more often than not a teleplay written for a completely different show than the one you’re actually submitting to, and generally the process would have an agent send that spec to the studio, where it would be evaluated and the writer’s skill considered. All that changed when executive producer Michael Piller threw open the doors to anyone and everyone with a story idea, giving newbie writers a shot at a sale – provided of course, that they followed the strict guidelines laid down for format and completed the required legal release forms.

Somewhere in London, a lad in his early twenties sat down in front of a mechanical typewriter and began brainstorming a story that pit Captain Picard and Wesley Crusher against a shape-changing alien invader…

The spec script program was such a hit that it created its own office to handle the tonnage of mail that arrived, with intakes of fifty to one hundred scripts a week not uncommon. The process works like this – each script, without exception, is reviewed by a reader, who puts together a report known as ‘coverage’, which in turn goes to the executive producer’s office for a look-over. If a script trips over any of the guidelines (such as page format or presentation style), it is automatically rejected before the story is even considered; passing that hurdle, the reader looks for a good story and the clear sign that the writer has a clue about the subject matter.

If the coverage is good, the spec script may be bought outright, or it may be rejected but the writer brought in if they show promise. The next hurdle is the polite hell of ‘pitching’, where the would-be writer must come up with a few short story synopses that could spin out in to full-blown scripts, then pitch them (in person or over the phone) to a story editor or staff writer.

When you consider that the writing team takes around 1,200 pitches a year, between 10 and 25 per week, with each potential pitchee throwing out at least three or more ideas each session, that’s roughly 4,000+ story ideas each season. Around 10% of those attract the staff’s attention, and less than 2% of those are considered possibly good enough to go the distance to become the basis for a teleplay…and even then your story may still not make it to air. Comparisons to winning the Lottery are not uncommon.

The rules for spec scripts on ST: TNG introduced a two-script maximum in 1992, and by that time I had taken my two shots and been rejected both times. My initial pitches were examples of rookie mistakes, relying too much on previous plotlines, and they were ‘passed’. I’d already finished a third script, but my time was up.

Rather less cocky than I had been, I went away and worked at learning the craft of screenwriting, attending a writer’s workshop in 1994 for hopefuls like myself. Lolita Fatjo joined staff writers Brannon Braga and Ron Moore in giving out sterling advice – Moore himself was a fannish success story after his sale of ‘The Bonding’ – and they encouraged us to try out for the newest Star Trek series, Deep Space Nine. I wasted no time, and penned a couple of specs…only to be stopped in my tracks by a polite-yet-to-the-point rejection letter. I’d had my three strikes and I was out.

Or so it seemed.

By this point, I’d been working as a freelance journalist on a number of genre media magazines, and my writing took me to the Star Trek production offices on several occasions. Interviewing scriptwriters and producers allowed me to slip in the odd question of my own about the business here and there, helping me to improve my work; it was enough that when Star Trek: Voyager got under way, I was allowed to buck the trend and try one last time.

I wrote a story about holographic invaders, and sent it off. And in return I got another rejection letter – a few more, and I could start wallpapering with them. But that last script opened the door for an invitation to pitch to the show, and over the next year I threw out 20 pitches with plots as diverse as time-travelling ghosts and invisible stowaways. Working with writers Joe Menofsky and Bryan Fuller, I came up with a story called ‘Perchance to Dream‘ and the rest was history; after a decade of dogged struggle, I had finally achieved a personal goal – to create a little piece of the Star Trek universe.

Post Script

Selling only a story premise means that typically the author is only credited on documentation for the episode, rather than on-screen; the reason for this is that Writer’s Guild guidelines are very specific about whose name appears on a title (or ‘card’ as they are known in the industry) for a television show. However, in 2002, I gained a little extra recognition of my contribution to Star Trek: Voyager, courtesy of Geoffrey Mandel’s book Star Trek Star Charts. A graphic artist on Voyager, Star Trek Insurrection and Enterprise, Geoff’s excellent book maps the galaxy of Star Trek, including the course plotted by Voyager‘s journey home; he very kindly named the Mutara-class cloud encountered by the crew during ‘One’ the Swallow Nebula, in honour of my story sale.